Topic 11.4. Management of testing for other relatives of a person with Friedreich ataxia

This chapter of the Clinical Management Guidelines for Friedreich Ataxia and the recommendations and best practice statements contained herein were endorsed by the authors and the Friedreich Ataxia Guidelines Panel in 2022.

Topic Contents

11.4 Management of testing for other relatives of a person with Friedreich ataxia

11.4.1 Testing of other relatives

11.4.2 Reproductive options for carrier couples

Disclaimer / Intended Use / Funding

Disclaimer

The Clinical Management Guidelines for Friedreich ataxia (‘Guidelines’) are protected by copyright owned by the authors who contributed to their development or said authors’ assignees.

These Guidelines are systematically developed evidence statements incorporating data from a comprehensive literature review of the most recent studies available (up to the Guidelines submission date) and reviewed according to the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment Development and Evaluations (GRADE) framework © The Grade Working Group.

Guidelines users must seek out the most recent information that might supersede the diagnostic and treatment recommendations contained within these Guidelines and consider local variations in clinical settings, funding and resources that may impact on the implementation of the recommendations set out in these Guidelines.

The authors of these Guidelines disclaim all liability for the accuracy or completeness of the Guidelines, and disclaim all warranties, express or implied to their incorrect use.

Intended Use

These Guidelines are made available as general information only and do not constitute medical advice. These Guidelines are intended to assist qualified healthcare professionals make informed treatment decisions about the care of individuals with Friedreich ataxia. They are not intended as a sole source of guidance in managing issues related to Friedreich ataxia. Rather, they are designed to assist clinicians by providing an evidence-based framework for decision-making.

These Guidelines are not intended to replace clinical judgment and other approaches to diagnosing and managing problems associated with Friedreich ataxia which may be appropriate in specific circumstances. Ultimately, healthcare professionals must make their own treatment decisions on a case-by-case basis, after consultation with their patients, using their clinical judgment, knowledge and expertise.

Guidelines users must not edit or modify the Guidelines in any way – including removing any branding, acknowledgement, authorship or copyright notice.

Funding

The authors of this document gratefully acknowledge the support of the Friedreich Ataxia Research Alliance (FARA). The views and opinions expressed in the Guidelines are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of FARA.

11.4 Management of testing for other relatives of a person with Friedreich ataxia

Martin B. Delatycki, Alexandra Durr, Paola Giunti, Grace Yoon and Susan E. Walther

11.4.1 Testing of other relatives

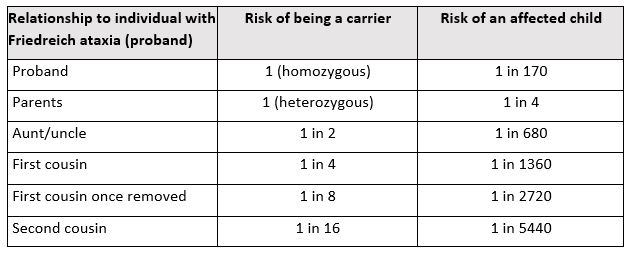

Table 11.1 lists the risk of being a carrier and the risk of having an affected child for a person with FRDA and their relatives. The calculated risk of having an affected child assumes that the partner of the individual with FRDA is unrelated and Caucasian, with a risk of being a carrier of 1 in 85. If the individual’s partner is related to them, the risk is likely to be considerably higher and needs to be calculated individually. If a relative is identified as a carrier, their partner should be offered carrier testing for the GAA expansion and the implications for reproductive planning should be discussed. If the partner is not a carrier of a GAA expansion, the risk that they are a carrier of a point mutation/deletion is about 1 in 4000 and the risk of having an affected child is about 1 in 16,000 (i.e., about double the risk of a Caucasian couple without a family history of FRDA). Sequencing of FXN can be offered to the partner in this situation. The person undergoing sequencing needs to be made aware of the risk of finding a variant of unknown significance; that is, a DNA sequence change where it cannot be determined if it is a disease causing pathogenic variant or a benign polymorphism. Some laboratories will agree to only report pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants and not variants of uncertain significance in the setting of carrier screening.

It is recommended that carrier testing be first undertaken on the closest relative as a negative result means that genetic testing of more distant relatives may not be necessary.

11.4.2 Reproductive options for carrier couples

Options available to couples where both are carriers of FXN pathogenic variants are as follows. Some or all of these options may not be available in some centers.

Prenatal diagnosis: this is generally done by chorionic villus sampling (CVS). Here the chorion (part of the developing placenta) is biopsied under ultrasound guidance. This tissue generally contains the same genome as the fetus. Less commonly, prenatal diagnosis is done using amniocentesis, where amniotic fluid is removed under ultrasound guidance. If the fetus is found to have two FXN pathogenic variants, the couple has the option of pregnancy termination. However, if the couple choose not to terminate the pregnancy, this is equivalent to pre-symptomatic testing of a minor. The issues discussed above in relation to pre-symptomatic testing of a minor are relevant to this situation and appropriate counseling is required.

Preimplantation genetic testing (PGT-M): In vitro fertilization is undertaken whereby the woman’s ovum is fertilized in vitro by the man’s sperm using intracytoplasmic sperm injection. The fertilized cell is allowed to multiply, resulting in a multicellular embryo. At this point, one or more cells are biopsied and tested for the presence of FXN pathogenic variants. This is generally done by an indirect linkage method called karyomapping, since it is not technically possible to identify large triplet repeat expansions in DNA from a single or few cells. Only embryos with one or no FXN pathogenic variants are available to be placed in the woman’s uterus. The fact that the chance of pregnancy is as low as 20% for each PGT cycle should be discussed with the couple. Since PGT is less accurate than prenatal diagnosis, couples are generally offered prenatal diagnosis following PGT.

Donor ovum, sperm or embryo: the use of donor gametes or embryos where the donor(s) are not carriers of a FXN pathogenic variant will greatly reduce the risk of a child being born with FRDA. If possible, the gamete or embryo donors should be tested for the FXN GAA expansion to ensure they are not a carrier and therefore the risk of FRDA in the child is low.

Adoption: this is an option that some couples will choose where the above options are unacceptable for various reasons.

Table 11.1: Carrier risk and risk of affected offspring for individuals with Friedreich ataxia and their relatives

Martin B. Delatycki, MBBS, FRACP, PhD

Co-Director, Bruce Lefroy Centre, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Parkville, Victoria, Australia Email: martin.delatycki@vcgs.org.au

Alexandra Durr, MD, PhD

Professor of Neurogenetics, Sorbonne Université, Paris, France

Email: alexandra.durr@icm-institute.org

Paola Giunti, MD, PhD

Professor, Queen Square Institute of Neurology, UCL, London, UK

Email: p.giunti@ucl.ac.uk

Susan E. Walther, MS, CGC

Genetic Counselor, Clinic for Special Children, Strasburg, Pennsylvania, USA

Grace Yoon, MD

Clinical Geneticist, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Email: grace.yoon@utoronto.ca

2. Candayan A, Yunisova G, Cakar A, Durmus H, Basak AN, Parman Y, et al. The first biallelic missense mutation in the FXN gene in a consanguineous Turkish family with Charcot-Marie-Tooth-like phenotype. Neurogenetics. 2020;21(1):73-8.

3. Delatycki MB, Paris DB, Gardner RJ, Nicholson GA, Nassif N, Storey E, et al. Clinical and genetic study of Friedreich ataxia in an Australian population. Am J Med Genet. 1999;87(2):168-74.

4. Dürr A, Cossee M, Agid Y, Campuzano V, Mignard C, Penet C, et al. Clinical and genetic abnormalities in patients with Friedreich’s ataxia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(16):1169-75.

5. Filla A, De Michele G, Cavalcanti F, Pianese L, Monticelli A, Campanella G, et al. The relationship between trinucleotide (GAA) repeat length and clinical features in Friedreich ataxia. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59(3):554-60.

6. Tsou AY, Paulsen EK, Lagedrost SJ, Perlman SL, Mathews KD, Wilmot GR, et al. Mortality in Friedreich ataxia. J Neurol Sci. 2011;307:46-9.

7. Arbour L, Canadian Paediatric Society, Bioethics Committee. Guidelines for genetic testing of healthy children. Paediatr Child Health. 2003;8(1):42-52.

8. Borry P, Evers-Kiebooms G, Cornel MC, Clarke A, Dierickx K, Public, et al. Genetic testing in asymptomatic minors: background considerations towards ESHG Recommendations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(6):711-9.

9. Borry P, Fryns JP, Schotsmans P, Dierickx K. Carrier testing in minors: a systematic review of guidelines and position papers. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14(2):133-8.

10. Botkin JR, Belmont JW, Berg JS, Berkman BE, Bombard Y, Holm IA, et al. Points to consider: ethical, legal, and psychosocial implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97(1):6-21.

11. Vears DF, Ayres S, Boyle J, Mansour J, Newson AJ, Education E, et al. Human Genetics Society of Australasia position statement: Predictive and presymptomatic genetic testing in adults and children. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2020;23(3):184-9.

12. Borry P, Stultiens L, Goffin T, Nys H, Dierickx K. Minors and informed consent in carrier testing: a survey of European clinical geneticists. J Med Ethics. 2008;34(5):370-4.

13. Ross LF. Carrier detection in childhood: a need for policy reform. Genome Med. 2010;2(4):25.

14. Borry P, Goffin T, Nys H, Dierickx K. Attitudes regarding predictive genetic testing in minors: a survey of European clinical geneticists. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2008;148C(1):78-83.

15. Mand C, Gillam L, Duncan RE, Delatycki MB. “It was the missing piece”: adolescent experiences of predictive genetic testing for adult-onset conditions. Genet Med. 2013;15(8):643-9.

16. Ackerman MJ, Priori SG, Willems S, Berul C, Brugada R, Calkins H, et al. HRS/EHRA expert consensus statement on the state of genetic testing for the channelopathies and cardiomyopathies this document was developed as a partnership between the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Heart Rhythm. 2011;8(8):1308-39.

17. Hershberger RE, Lindenfeld J, Mestroni L, Seidman CE, Taylor MR, Towbin JA, et al. Genetic evaluation of cardiomyopathy–a Heart Failure Society of America practice guideline. J Card Fail. 2009;15(2):83-97.

18. Lowe GC, Corben LA, Duncan RE, Yoon G, Delatycki MB. “Both sides of the wheelchair”: The views of individuals with, and parents of individuals with Friedreich ataxia regarding pre-symptomatic testing of minors. J Genet Couns. 2015;24(5):732-43.

These Guidelines are systematically developed evidence statements incorporating data from a comprehensive literature review of the most recent studies available (up to the Guidelines submission date) and reviewed according to the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment Development and Evaluations (GRADE) framework © The Grade Working Group.

This chapter of the Clinical Management Guidelines for Friedreich Ataxia and the recommendations and best practice statements contained herein were endorsed by the authors and the Friedreich Ataxia Guidelines Panel in 2022.

It is our expectation that going forward individual topics can be updated in real-time in response to new evidence versus a re-evaluation and update of all topics simultaneously.